Supreme Court should consider Indian senior citizens "right to die with dignity"

Sat 10 Mar 2018, 17:26:33

In the seventies when I was in charge of the weekend edition of Indian Express called Sunday Standard, a Sikh gentleman entered the office one morning and asked to see me. He was in his late seventies and fairly fit if a little frail. We got talking, and he said that he wanted to seek the permission of the Supreme Court to allow him to die on his terms.

Having lived a life that was full and satisfying, he was now being parceled from one child to another and he found it mortifying and deeply insulting. He related how his wife had passed away and just recently he had overheard his son-in-law asking his wife when the old man’s time was up with them, and that he should shift to his son’s city.

"I just want to go with my dignity intact," he said, adding, "but I do not wish to break the law and I need this newspaper’s help".

We shared a cup of tea and he whispered conspiratorially that he thought his daughter-in-law intended to convert the garage into his room when he went to his son’s place next week, and that he did not wish to suffer that insult. "My son is weak," he said. "He will not stand up for me."

There was no regret or emotion. Just plain fact.

We tried to hire a lawyer but nothing really happened. He never got the official permission. Several years later, I was told about a family where the mother was left stranded at the airport while her son and his children flew out of the country. She sat on a bench hours waiting for the son who had told her he was going to get her ticket. A doctor at Max once told me that it was far more common than believed for grown-up children to leave their parents at a hospital and

vanish. The elderly persons are often unable to offer any details of their whereabouts.

vanish. The elderly persons are often unable to offer any details of their whereabouts.

These are dimensions to assisted euthanasia or passive support for pulling the plug, that form an integral part of the Supreme Court’s decision to allow it but are not factored into the permission.

The honorable court has its heart in the right place, but it is not always the extreme case as symbolized by Aruna Shanbaug who lay in a coma for 26 years. In which year would the family have decided that it was over?

Dignity in death is not given in a nation like ours, which is currently in flux, especially with its traditional cultural bastions being battered by the advent of technology and the collapse of the larger family. The equation between children and parents are changing rapidly. There is almost no infrastructure for the elderly and the infirm. Caring for aged parents comes with very little guarantee of love now, and even when they are tolerated, it is served as an adjunct to lip service respect. Forget about sibling rivalry, in this era children take parents to court for slights, real and imagined.

It is not just a medical issue — in which a patient whose chances of making a comeback have dwindled to zero — where euthanasia is an option. Dignity crosses into the other aspects of the living. All passion spent, and ready to go, it's better to shuffle off the mortal coil than being treated like a used tissue. More of the same, day after day, there comes a point where the body starts to let you down and you do not like yourself. With treatments like chemotherapy, dialysis, etc, life becomes a regimen that promises nothing but an extension of the torture.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from World

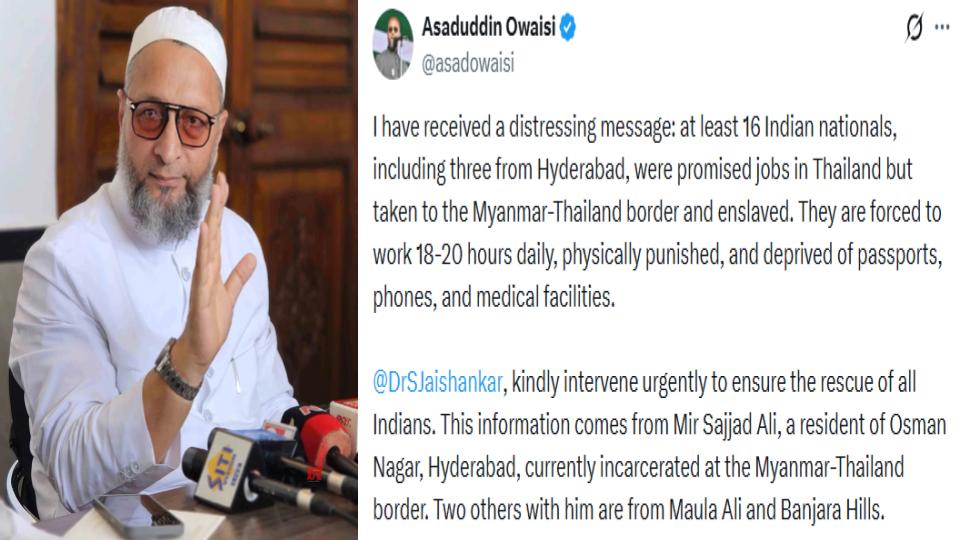

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Is it right to exclude Bangladesh from the T20 World Cup?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)