Indian media accused of Islamophobia for its coronavirus coverage

Mon 18 May 2020, 21:58:32

.jpg)

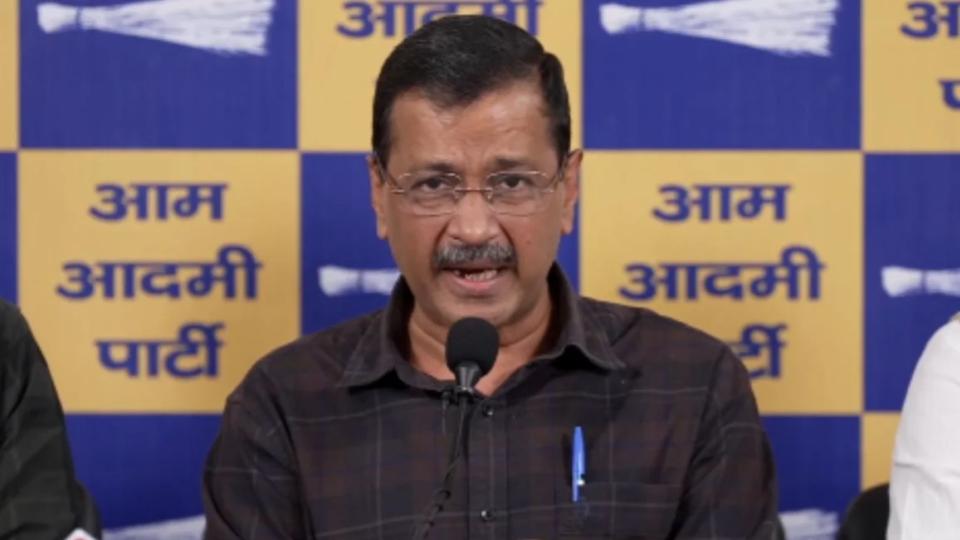

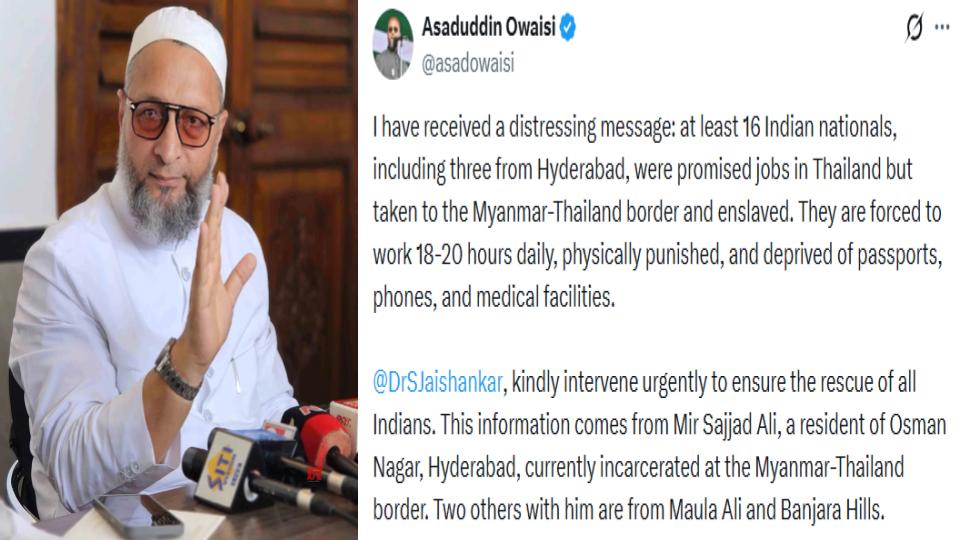

"During this lockdown, why does every crowd gather only near mosques?" journalist Arnab Goswami recently asked on the Indian news channel, Republic TV.

The well-known anchor was referring to a crowd that had gathered last month near a railway station that happens to be near a mosque in Mumbai, the capital of the western state of Maharashtra.

Local media reports said they were migrant workers desperate to get back to their towns and villages weeks after a nationwide lockdown was imposed to try and combat the spread of the coronavirus.

The lockdown had left most of them jobless. They assembled there after hearing rumours that the government had finally arranged transport for their return home.

Just days earlier, similarly, anxious workers rioted in neighbouring Gujarat state, but the media did not link it to any particular religion, as was the case in Mumbai.

As a news website, Newslaundry's Atul Chaurasia noted on his show: "The Mumbai incident once again brought to the fore the diseased, sectarian face of channels, because in the background they had spotted a mosque."

Critics have accused a large section of Indian media of blaming Muslims for the spread of the coronavirus, which so far has infected more than 82,000 people in the country and caused 2,649 deaths.

Islamophobia during a pandemic:

Coronavirus worries took centre stage in India by the third week of March but the preceding months had already been turbulent.

Pan-India protests erupted in December 2019 against a new citizenship law championed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, that many deemed discriminatory.

Anti-Muslim mob violence shook Delhi in February after supporters of a governing party leader allegedly attacked peaceful sit-ins against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA).

As the world was coming to terms with the sweeping pandemic and its effects, sections of news media remained embroiled in divisive debates until March 24, the day police cleared out the last vestiges of the anti-CAA protest sites led by Muslims in New Delhi.

A nationwide lockdown was implemented at midnight on March 24.

By late March, Muslims became the focus of media attention after it emerged that six people who died from COVID-19 in southern Telangana state had attended an event held by a Muslim religious group called Tablighi Jamaat from March 13-15 in New Delhi.

Muslims faced further vilification in the first week of April after a government spokesperson publicly linked a spike in coronavirus cases to the Jamaat event, which was also attended by preachers from other Muslim countries.

Since then, the government seemed to have singled out the Jamaat at most official briefings.

"The media chose not to ask the government why foreign participants were not tested at airports, why Delhi and the central government and police agencies gave permission for the gathering, which was denied by the Maharashtra government," activist Kavita Krishnan told Al Jazeera.

Trending Twitter hashtags, such as #CoronaJihad, soon appeared on TV screens.

"The media are distorting facts to suggest that every Muslim belongs to Tablighi Jamaat, every Muslim is responsible for the coronavirus, and coronavirus is a synonym for Muslim," said political analyst Shahid Siddiqui.

Though on March 13 the government had said COVID-19 is "not a health emergency" and the lockdown was announced days after the Jamaat event, Siddiqui called the group "irresponsible, callous and foolish" for holding a mass meeting when social distancing advisories were already widely disseminated.

He said, however, that he was "shocked" at journalists pinning the blame for the outbreak on the Jamaat, and by association, Muslims.

Disproportionate focus:

Senior health journalist Vidya Krishnan is a rare voice in the media pointing to the government's inordinate focus on the Jamaat.

Krishnan explained that the reason a large percentage of coronavirus-positive cases in India was being linked to the group is because of aggressive contact tracing of Jamaat attendees by the government, whereas citizens who have crossed paths with patients unconnected to the Jamaat were not being tracked and tested with equal determination.

"What the Indian government has been doing during the pandemic is just the next step in the kind of persecution of minorities that has been happening under the Modi administration," she told Al Jazeera.

"You cannot isolate the February riots in Delhi from what happened through much of April in everyday media briefings where the Health Ministry and Home Ministry were actively painting a target on the backs of one community."

On April 19, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) expressed concern about "anti-Muslim sentiments and Islamophobia within political and media circles and on mainstream and social media platforms" in India.

After the OIC statement, the government began addressing the issue. Krishnan explained that the authorities then repeatedly spoke about how stigmatisation is not good "but didn't exactly stop giving out the number of Tablighi Jamaat infections. Now it seems like the blame has shifted to poor migrants who are moving and vegetable vendors who are now being called 'super spreaders', and the briefings have become erratic as cases spiral."

She added: "This is a continuing pattern of blaming those who get infected instead of taking humane and scientific remedial measures like affordable healthcare, better contact tracing and putting data in the public domain."

In the past two months, a spate of false reports on social media and news media about Muslims spitting, roaming naked or defecating in public have been debunked.

The falsehoods are so numerous that even police departments and other official agencies have been countering or correcting tweets by news organisations and their

representatives.

representatives.

While studying debunked COVID-19 stories in India, University of Michigan associate professor Joyojeet Pal and his co-researchers found a rise in misinformation about Muslims from about the end of March.

In the mainstream media, "the truly insidious part is the way in which Islamophobia is suggested, without explicit mention," Pal said.

"This could include the selection of participants for TV debates, which allows an anchor to claim neutrality, but have participants indulge in extreme claims that go unchallenged. Or the use of imagery - like the focus on a mosque near a train station where migrants gathered as if to suggest that Muslims had something to do with the gathering."

On April 10, on Zee News, anchor Sudhir Chaudhary openly accused Muslims of impeding India's coronavirus war.

Among the evidence he offered was a video of a Muslim-dominated area of New Delhi - he conceded that hardly anyone was visible in his visuals of the lockdown from this otherwise always-packed locality, but still added: "These people defy the law just so that the infection will spread rapidly across the country."

That same day, India Today network aired a so-called "investigation", titled Madrasa Hotspots, on Islamic schools in and around New Delhi, revealing that they misled police about the number of children in their care during the lockdown and rebuking them for renouncing social distancing and online classes.

The report did not acknowledge what filmmaker-writer-activist Saba Dewan pointed out - that "madrasas are for orphans or children of the very poor" and therefore, far from having personal computers, internet connections and spacious homes, those children might starve if sent away during the lockdown.

Dewan added: "There's no data showing that madrasas are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 and not, for instance, boarding houses run for poor but upper-caste Hindu children in Varanasi (in Uttar Pradesh state) that are also congested. The decision to put the spotlight on madrasas alone was absolutely Islamophobic."

The pushback against such journalism has been occasionally intense.

Earlier this month, for instance, police from the southern state of Kerala registered a complaint against Zee’s Chaudhary for making incendiary remarks about the Muslim minority on a show in which he described the types of jihad practised by the community.

Police in Maharashtra state registered a complaint against Republic’s Goswami for the programme mentioned at the start of this article.

Rahul Kanwal, who anchored Madrasa Hotspots, was criticised on Twitter for airing the show.

"There are so many hotspots in India - we aren't naming them to link them with a particular community. Not only is such a usage Islamophobic, but it also associates the incidence of COVID-19 with stigma, it criminalises victims of a disease," Kavita Krishnan told Al Jazeera.

"There's been so little testing in India, which also creates room for this dangerous stigma. Dangerous because it deters people from coming forward to seek testing and help, for fear of being tarred by the same brush of crime or shame," Krishnan added.

The media's portrayal of Muslims as potential vectors of the virus has had real consequences.

Reports have emerged of Muslims being beaten, vegetable vendors chased from Hindu communities, a pregnant woman losing her baby after a hospital turned her away because she was Muslim and another hospital segregating COVID-19 patients by religion.

Since the OIC statement, the mainstream news media appears to have gone slow on accusing Muslims of spreading COVID-19 in India. However, the tide of misinformation and propaganda about the community on social media platforms has not stopped.

'Seeped into their soul':

Goswami, Chaudhary, Kanwal, news agency ANI's Smita Prakash, India TV's Rajat Sharma and News Nation's Deepak Chaurasia were contacted for comments by Al Jazeera. Only Chaurasia agreed to be interviewed.

Asked if his TV show questioned why no other Indian gathering has been subject to the meticulous contact tracing done with Jamaat attendees, he said: "If what you say about contact tracing is true, then it's my request to the government."

"We have raised the matter of every other such group, the media has raised these matters," Chaurasia insisted, citing criticism of a singer who defied self-isolation to attend functions in March and a BJP politician who was at one such event.

But the media has avoided villainising non-Muslim communities for the multiple political, social and religious congregations other than the Jamaat event held in India before and even after the lockdown.

The BJP's Lalitha Kumaramangalam disagrees with criticism of the government in this matter but says that the pandemic coverage is biased. "Unfortunately, Tablighi Jamaat belongs to a particular community and have to be called out," she told Al Jazeera.

"I have good friends among Muslims," she added. "My father's favourite junior was called Ali Mohammed. Ali Maama [uncle] was our favourite, so it's not that I'm prejudiced against Muslims. Unfortunately, too many from that community are behaving badly, and bad news seems to sell."

Later in the interview, she said she had heard that falsehoods were being floated about Muslim misbehaviour.

Salman Anees Soz of the main opposition Congress party said he believed the Jamaat issue was kept on the boil for as long as it was to distract Indians from the government's

"bungled response [to COVID-19]".

"Some years back, I would have said maybe the media just wanted to be on the right side of the government. Now I think many important media outlets genuinely believe Islamophobia is the way to go," he told Al Jazeera.

Soz says while such media are acting as instruments of the government, "at some level, Islamophobia has seeped into their soul".

Thanks: AL JAZEERA

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from Specials

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Which cricket team is your favourite to win the T20 World Cup 2026?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)