Baghdad: ISIL claims attack in busy Sadr City market

Tue 03 Jan 2017, 18:19:23

Mosul, Iraq - As fighting raged in eastern Mosul on a recent afternoon, a black Humvee arrived at an Iraqi army command post with a collection of plastics, electronics and rotor blades lashed to its back.

Soldiers leaped to unload the cargo, which comprised the remnants of the latest tool in ISIL's armoury: drones.

The haul included a number of small devices of the kind favoured by filmmakers and hobbyists, costing a few hundred dollars apiece. But there were also larger, fixed-wing craft fashioned out of corrugated plastic and duct tape, apparently made by the fighters themselves.

Since mid-2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS) group has held Mosul, after sweeping through northern Iraq in a shock offensive.

It is now their last urban stronghold in the country, and for more than two months, the Iraqi army's operation to retake the city has met fierce resistance, including snipers, ambushes and suicide attacks using explosive-laden trucks. Drones have been used for reconnaissance and to relay instructions to suicide bombers, said General Abdul Wahab al-Saadi, a commander with the elite counterterrorism service in eastern Mosul.

"They use them to give directions to suicide car bombs coming towards us, as well as to take pictures of our forces," Saadi told Al Jazeera.

In the past, ISIL has used drones in Iraq and Syria for general intelligence-gathering, as spotters for mortar firing, and even for filming propaganda videos. Soldiers have regularly spotted these drones over army positions on the outskirts of Mosul, prompting bursts of gunfire skywards.

But there is a fresh threat, Saadi said: ISIL has begun to use the drones themselves as weapons. "They also use a new tactic, where the drone itself has a bomb attached to it," he explained.

This has already proven lethal. Last October, after Kurdish Peshmerga fighters downed an ISIL drone north of Mosul and began transporting it back to their base for examination, a small amount of explosive material inside the device detonated, killing two Kurdish fighters and injuring two French special forces soldiers with whom they had been working. These were the first reported casualties from one of ISIL's weaponised drones.

Several of Iraq's allies, including the United States and the United Kingdom, have long flown drones in the country for both attacks and observation. Even Saadi's own men use small craft for reconnaissance, he said.

But American forces leading the anti-ISIL coalition have been slow to realise the threat posed by the armed group's drone use, said PW Singer, a senior fellow at the New America

Foundation and an expert in robotic warfare. "We've known of non-state actors ... using drones for years," he told Al Jazeera. "We've also known that the commercial spread of the technology made it possible for anyone to buy [them]," yet the rush towards countermeasures began only recently, he added.

The defence department last July asked Congress for an extra $20m to help tackle the threat posed by ISIL's use of unmanned aircraft, and Lieutenant General Michael Shields, director of the US Joint Improvised-Threat Defeat Organization, told reporters in October that there was "a sense of urgency" in equipping US troops with anti-drone technology.

New countermeasures have been implemented, including Battelle's Drone Defender, a hand-held directed-energy device that can knock drones out of the sky at a distance of 400 metres. The device has already been deployed with US troops in Iraq.

Saadi, meanwhile, says that his soldiers are usually able to disable ISIL's drones by using sniper rifles or machine guns.

"We don't think that it is very dangerous. ISIL collects information about our forces, and we destroy the drones before they come to us," he said.

Soldiers leaped to unload the cargo, which comprised the remnants of the latest tool in ISIL's armoury: drones.

The haul included a number of small devices of the kind favoured by filmmakers and hobbyists, costing a few hundred dollars apiece. But there were also larger, fixed-wing craft fashioned out of corrugated plastic and duct tape, apparently made by the fighters themselves.

Since mid-2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS) group has held Mosul, after sweeping through northern Iraq in a shock offensive.

It is now their last urban stronghold in the country, and for more than two months, the Iraqi army's operation to retake the city has met fierce resistance, including snipers, ambushes and suicide attacks using explosive-laden trucks. Drones have been used for reconnaissance and to relay instructions to suicide bombers, said General Abdul Wahab al-Saadi, a commander with the elite counterterrorism service in eastern Mosul.

"They use them to give directions to suicide car bombs coming towards us, as well as to take pictures of our forces," Saadi told Al Jazeera.

In the past, ISIL has used drones in Iraq and Syria for general intelligence-gathering, as spotters for mortar firing, and even for filming propaganda videos. Soldiers have regularly spotted these drones over army positions on the outskirts of Mosul, prompting bursts of gunfire skywards.

But there is a fresh threat, Saadi said: ISIL has begun to use the drones themselves as weapons. "They also use a new tactic, where the drone itself has a bomb attached to it," he explained.

This has already proven lethal. Last October, after Kurdish Peshmerga fighters downed an ISIL drone north of Mosul and began transporting it back to their base for examination, a small amount of explosive material inside the device detonated, killing two Kurdish fighters and injuring two French special forces soldiers with whom they had been working. These were the first reported casualties from one of ISIL's weaponised drones.

Several of Iraq's allies, including the United States and the United Kingdom, have long flown drones in the country for both attacks and observation. Even Saadi's own men use small craft for reconnaissance, he said.

But American forces leading the anti-ISIL coalition have been slow to realise the threat posed by the armed group's drone use, said PW Singer, a senior fellow at the New America

Foundation and an expert in robotic warfare. "We've known of non-state actors ... using drones for years," he told Al Jazeera. "We've also known that the commercial spread of the technology made it possible for anyone to buy [them]," yet the rush towards countermeasures began only recently, he added.

The defence department last July asked Congress for an extra $20m to help tackle the threat posed by ISIL's use of unmanned aircraft, and Lieutenant General Michael Shields, director of the US Joint Improvised-Threat Defeat Organization, told reporters in October that there was "a sense of urgency" in equipping US troops with anti-drone technology.

New countermeasures have been implemented, including Battelle's Drone Defender, a hand-held directed-energy device that can knock drones out of the sky at a distance of 400 metres. The device has already been deployed with US troops in Iraq.

Saadi, meanwhile, says that his soldiers are usually able to disable ISIL's drones by using sniper rifles or machine guns.

"We don't think that it is very dangerous. ISIL collects information about our forces, and we destroy the drones before they come to us," he said.

Although ISIL's drone fleet so far appears relatively basic, it could be developed further in the months ahead. Researchers from the UK-based Conflict Armament Research (CAR) group documented an ISIL "drone workshop" in Ramadi last February, where fighters had been attempting to build larger drones with potent explosive payloads crafted from the warheads of anti-aircraft missiles.

This suggests that commercially available drones are not fitting ISIL's tactical needs, said CAR's managing director, Marcus Wilson.

"The other models they're trying to build are predominantly fixed-wing craft, which might allow for increased range or provide the ability to add a payload rather than just surveillance abilities, which is what we've observed in [our] report," Wilson told Al Jazeera.

He said that further development seems likely, especially given ISIL's history of designing complex components for weapons such as improvised explosive devices and producing them on an industrial scale.

"If they continue along this path, then we should be worried, because they still have a strong research and development capacity, have advanced their production abilities in the past, and still have the workshops capable of building sophisticated devices," Wilson said.

Still, even with further development, ISIL would likely be unable to produce more than what Singer describes as "small aerial IEDs" - unlikely to cause mass casualties or alter the balance of power.

This suggests that commercially available drones are not fitting ISIL's tactical needs, said CAR's managing director, Marcus Wilson.

"The other models they're trying to build are predominantly fixed-wing craft, which might allow for increased range or provide the ability to add a payload rather than just surveillance abilities, which is what we've observed in [our] report," Wilson told Al Jazeera.

He said that further development seems likely, especially given ISIL's history of designing complex components for weapons such as improvised explosive devices and producing them on an industrial scale.

"If they continue along this path, then we should be worried, because they still have a strong research and development capacity, have advanced their production abilities in the past, and still have the workshops capable of building sophisticated devices," Wilson said.

Still, even with further development, ISIL would likely be unable to produce more than what Singer describes as "small aerial IEDs" - unlikely to cause mass casualties or alter the balance of power.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

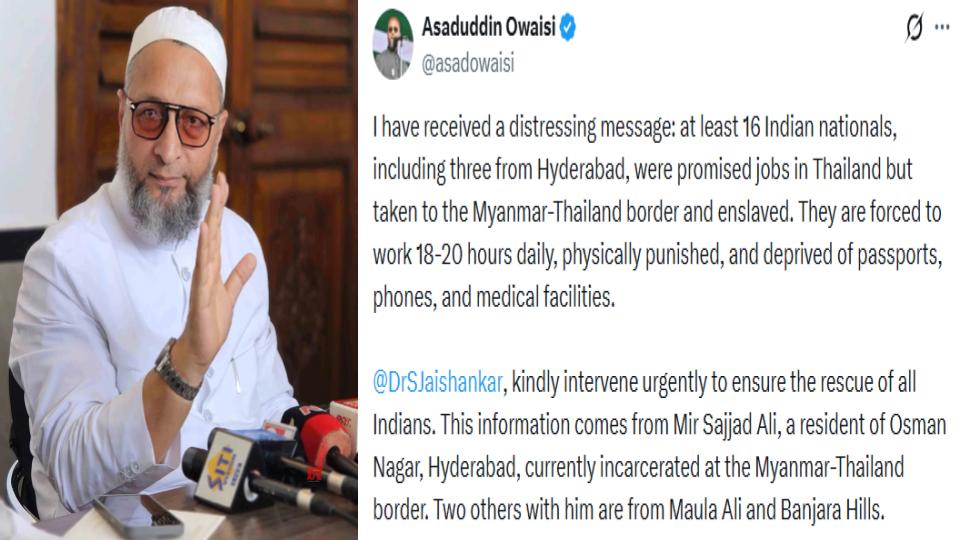

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Which cricket team is your favourite to win the T20 World Cup 2026?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)