How pubs and hotels are coping with SC's highway liquor ban

Sat 08 Apr 2017, 14:39:34

On March 31, guests staying at a five-star in Gurugram were taken by surprise when the hotel staff came frantically knocking on their doors. After a hurried explanation, the staff quickly emptied the mini-bars in their rooms of all alcoholic beverages.

At 6 that evening, the Supreme Court had ruled that no liquor would be sold in hotels and restaurants, besides liquor vends, falling within 500 metres of state and national highways. The ban would be effective from midnight. The hotel fell within the 500-metre limit. The staff had barely six hours to act.

The order has punched a massive hole in the country’s alcohol economy: manufacturers, distributors, vendors, restaurants, pubs, bars, hotels. A million jobs are in peril, some of the affected people say, and the pubs will be shorn of business worth Rs 10,000 to Rs 15,000 crore in the next one year. The state governments, too, stand to lose sizeable revenue — the prospects have sent many of them to devise ways to circumvent the ban.

A week later, most of the affected bars and pubs have complied with the Supreme Court order and stopped serving alcohol, some have decided to relocate to kosher sites away from the highway, while a few ingenious ones have started to work around the order — the infamous Indian jugaad is in play once again.

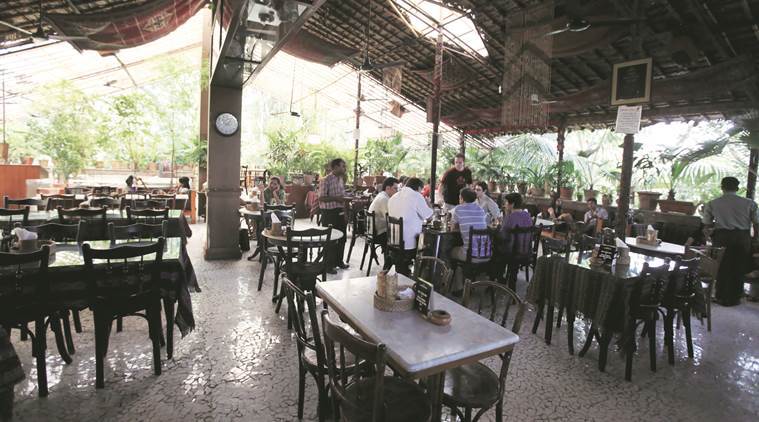

DLF CyberHub in Gurugram, the toniest wining and dining address in the National Capital Region, was teaming with revellers when the Supreme Court order cut the party short. Of the 50 restaurants, bars and pubs here, 34 served liquor.

A barricade and a “No entry” board stand at what was until last week the entrance to CyberHub on National Highway 8 that runs from Delhi to Jaipur. The exit, which was even closer to the highway, also lies blocked with a concrete wall. Visitors are now required to drive past CyberHub and then take a U-turn to reach the new entrance. It is a good one-kilometre drive from the highway to the first point that serves alcohol inside: The Wine Company. Currently, till the air is cleared, this trendy joint is trying to woo people with free mocktails.

At Farzi Café, the bar is empty. Making a weak attempt at humour, an employee asks: “Fruit beer? Considering that we cannot offer you actual beer.” The café, known for its inventive cocktails, is now focusing on its food and molecular gastronomy preparations. But that cannot make up for the loss of business.

Zorawar Kalra, the founder of Massive Restaurants which owns Farzi Café, says four of his restaurants have been affected, including one in Mumbai that is in the design stage and another in Chandigarh which is almost ready. “This has been the most damaging blow in the history of the Indian hospitality business,” he says.

A closed liquor shop in Mumbai. Photo: Sanjay K Sharma A closed liquor shop in Mumbai. Photo: Suryakant Niwate Not far from Farzi Café is The Beer Café. It is at an even greater disadvantage because it does not have food to fall back on. “Bar Closed” read the signs here amid whacky quotes like “24 hours in a day, 24 beers in a case. Coincidence?”. The café, which stocks over 50 brands from 19 countries, would sell its first pint at 11:30 am and the last around midnight. “Ab sukha pad gaya hai (Now, it’s a drought),” someone remarks.

“April 1 was our fifth anniversary here. And this was the anniversary gift we got,” says Tarun Tomar, the manager, smiling bleakly. He is worried about his future — his family of four includes two daughters, aged seven months and four years.

Employee morale has taken a severe blow. “We have daily staff briefings before the start and at the end of the day. These now include pep talks and the assurance that everything will work out fine,” says Sonal Dagar, assistant manager at Social Bar and Café that is owned by Riyaaz Amlani, president of the National Restaurant Association of India, or NRAI. A sign at the bar reads: “Dry day”.“The bartenders are feeling pretty jobless with only lemonade and iced-tea to make,” says Dagar.

Across the highway from CyberHub, the Trident and The Oberoi have closed the original entrances and have posted uniformed guards along the road to direct visitors to the new one. Each of these guards carries a placard with Trident and The Oberoi written on it in their trademark fonts. The new access is further down, through a narrower road to the left. It used to be the staff entrance, says an employee.

Also on the highway falls the Leela Ambience Hotel. The entrance to this hotel too has been shut and visitors now have to drive around a residential complex — the Ambience Lagoon apartments — to enter it, much to the displeasure of the residents.

A guard outside Trident and The Oberoi in Gurugram holds a placard to guide visitors to the new entrance away from the highway. Photo: Sanjay K Sharma A guard outside Trident and The Oberoi in Gurugram holds a placard to guide visitors to the new entrance away from the highway. Photo: Sanjay K Sharma While hotels and restaurants are hopeful that pushing back the entrances will solve the problem, the excise department isn’t giving any such assurance. S C Dahiya, the deputy excise and taxation commissioner of Gurugram, says his people will approve the entrance only if it is mentioned in the city’s development master-plan. If not, there is little hope of relief.

So far, 25 restaurants in Gurugram have surrendered their liquor licences. Some have shut shop, while a few have decided to relocate.

April was supposed to be a busy month for the country’s bars and pubs. As the mercury rises across the great plain, people would troop in for chilled beer and icy cocktails, and watch the 10th season of the Indian Premier League on the giant

screen. Those along the highways will be deprived of that meaty business.

screen. Those along the highways will be deprived of that meaty business.

Some states have decided to lend a helping hand. West Bengal, for one, has reclassified 277.3 km of state highways as arterial roads, bringing them under the administration of municipalities and panchayats to bypass the Supreme Court order. The notice is dated March 16, a fortnight before the ban was imposed.

The state government has also dropped stretches of 21-km Eastern Bypass from the list of state highways. In doing so, it has managed to save several popular hotels such as the Hyatt Regency, ITC Sonar Bangla, JW Marriott and The Gateway Hotels & Resorts.

West Bengal earns around Rs 3,200 crore as excise tax from the sale of liquor — its anxiety is understandable. According to the West Bengal Foreign Liquor Manufacturers, Wholesalers and Bonders’ Association, the government’s move will help at least 40 per cent of the 2,100 bars and restaurants affected by the ban, and at least 2,000 jobs will be saved.

Like West Bengal, the Punjab government has rechristened 30 km of state highways as “urban roads”. Similarly, on March 22, the Rajasthan Public Works Department declared 25 sections from 21 state highways in 16 districts as urban roads.

Maharashtra, too, is considering reclassifying parts of the state highways passing through big cities and towns. “We are waiting for an appointment with Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis to request de-notification of highways,” says Adarsh Shetty, president of the Indian Hotel and Restaurant Association.

At least 450 bars and permit rooms have been impacted around Mumbai, including areas along the Western Express Highway and Eastern Express Highway. The number of establishments affected in Maharashtra stands at 16,000.

About 60 per cent of the owners had taken loans worth several lakhs. To move 500 metres inside, they will have to sell the current space, and apply afresh to shift several licences. “It is practically impossible,” says Shetty.

At Thane’s Viviana Mall, just off the Eastern Express Highway, the coffee shops appear more crowded than usual. The resto-bars, by contrast, are empty. His establishment’s entire concept hinges on beer, rues Dharm Singh, the manager of a brewpub here, pausing to show on his mobile phone reactions on the court ruling on social media. The heady scent of malt and the many mugs and pitchers of beer, which account for some 70 per cent of sales here, are absent. So are the customers and music that typically fill the space. The employees, newly at risk of losing their jobs, polish already-clean tables.

Chandigarh, from where it all started, is in a fix. About 20 years ago, the Chandigarh Administration had notified all major roads as state highways in order to receive Central funds for their maintenance. After the Supreme Court order, it set up a committee to reverse that decision. The committee has given a go-ahead to reclassify these state highways as “major district roads”.

However, Harman Sidhu, on whose petition the Supreme Court issued the 500-metre verdict, challenged the move in the Punjab and Haryana High Court. After it dismissed his plea, Sidhu has taken the matter to the Supreme Court where it will be heard on April 17.

Riyaaz Amlani

‘Forget ease of doing business, we are now concerned about the guarantee of doing business’

Riyaaz Amlani, President, NRAI

In Karnataka, the timing of the ban has made the scenario particularly bitter-sweet: the recent state budget had abolished value-added tax on wine and beer. Retailers had hoped this would grow the market leaps and bounds. Now, some of that enthusiasm has been dampened.

Whether it is the wine and beer bars on Hosur Road, which is part of India's longest running national highway from Srinagar to Kanyakumari, or the liquor shops on Bannerghatta Road, one of the state highways, business remains brisk — for now. Noticing that different states have different excise years, the apex court has granted an extension to the states where the excise year extends beyond April. While Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh have till the end of June to comply with the order, Telangana has time till September 30.

Those that already comply with the order can barely conceal their glee. On the outskirts of Bengaluru, on the highway to Mysuru, staff at the plush Eagleton golf resort has never been happier about their long driveway. “It’s almost 2 km away, so that keeps us out of the purview,” says GP Mathew, the manager. However, India's largest beer maker, United Breweries, majority-owned by Heineken, says its sales could drop by 40 per cent.

“Don’t grant any new licences. But allow those who already have licences to continue for five years until they can move,” says Ralph Pinto, owner of Maracas in Goa, who spent Rs 20 lakh last September to redecorate his tapas bar located on National Highway 17. Since the last weekend, one in three groups of customers is walking out because they cannot sample any of the signature cocktails here. Pending bills and salaries worry Pinto, who says he will have to pack up if no exemptions are made to the Supreme Court order.

The chances are remote. Prohibition, as the experience from Bihar tells us, is a huge hit with women voters. So, the National Democratic Alliance government, which is forever on election mode, is unlikely to challenge the order. Goa, it is learnt, is unwilling to reclassify roads because it wants central funds to upgrade its road network.

As frustration and insecurity mounts, Amlani of NRAI says: “Forget ease of doing business, we are right now concerned about the guarantee of doing business.”

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from Business

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Should there be an India-Pakistan cricket match or not?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)