Turkey set to end state of emergency, replace it with harsh new ‘anti-terrorism’ legislation

Wed 18 Jul 2018, 12:22:58

Turkey’s state of emergency, imposed after the failed 2016 coup, is set to end — but the opposition fears it will be replaced by legislative measures that are even more repressive.

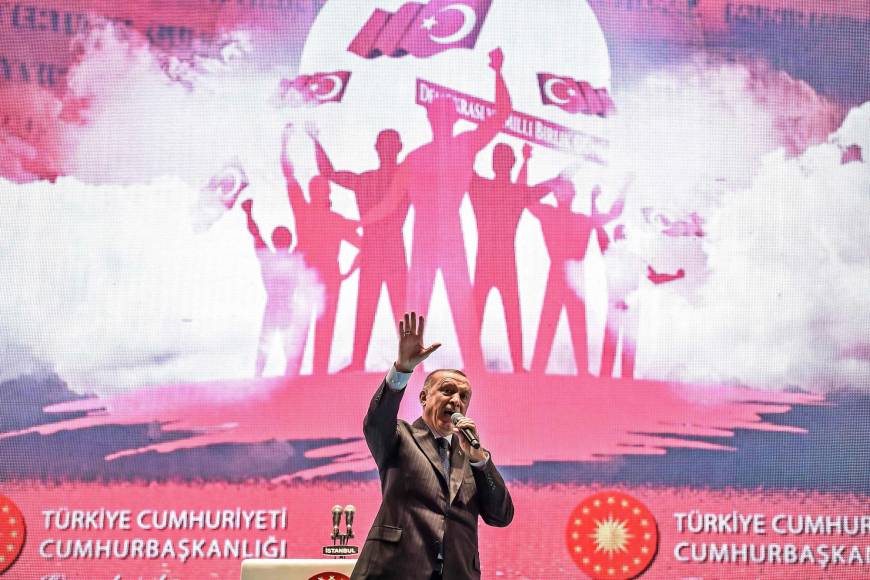

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared the state of emergency on July 20, 2016, five days after warplanes bombed Ankara and bloody clashes broke out in Istanbul in a doomed putsch that claimed 249 lives.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared the state of emergency on July 20, 2016, five days after warplanes bombed Ankara and bloody clashes broke out in Istanbul in a doomed putsch that claimed 249 lives.

Under the emergency measure, which normally would have lasted three months but was extended seven times, 80,000 people have been detained and about double that number have been fired from public institutions.

The biggest purge of Turkey’s modern history has targeted not just alleged supporters of Fethullah Gulen, the U.S.-based preacher blamed for the coup, but also Kurdish activists and leftists.

The former leaders of the opposition pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) — Figen Yuksekdag and Selahattin Demirtas — are still languishing in jail following their arrest in November 2016 on charges of links to Kurdish militants.

During the campaign for last month’s presidential election, which he won, Erdogan pledged that the state of emergency would end.

And it will — at 1 a.m. on Thursday, simply by virtue of the government not asking that it be extended.

But the opposition has been angered by the government’s submission of new legislation that apparently seeks to formalize some of the harshest aspects of the emergency.

The bill, dubbed “anti-terrorism” legislation by pro-government media, will be discussed at the commission level on Thursday and then in plenary session on Monday.

The main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), said the new measures would amount to a state of emergency on their own.

“With this bill, with the measures in this text, the state of emergency will not be extended for three

months but for three years,” said the head of the CHP’s parliamentary faction, Ozgur Ozel. “They make it look like they are lifting the emergency, but in fact they are continuing it.”

Under the proposed legislation, the authorities would retain for three more years the power to fire civil servants deemed linked to “terrorist” groups, retaining a key power of the state of emergency.

Protests and gatherings would be banned in open public areas after sunset, although they could be authorized until midnight if they did not disturb the public order.

Local authorities would be able to prohibit individuals from entering or leaving a defined area for 15 days on security grounds.

And suspect could be held without charge for 48 hours — or up to four days in the case of multiple offenses. This could be extended twice if there was difficulty in collecting evidence or if the case was deemed to be particularly voluminous.

The authorities have also shown no hesitation in using the special powers of the emergency — right up to its final days.

Following a decree issued on July 8, 18,632 people were fired — 8,998 of them police officers — over suspected links to terrorist organizations and groups that “act against national security.”

The move came just two weeks after Erdogan was re-elected under a new system that gives him greater powers than any Turkish leader since the aftermath of World War II.

The new executive presidency means government ministries and public institutions are now centralized under the direct control of the presidency.

Erdogan says it is necessary to have a more efficient government, but the opposition claims it has placed Turkey squarely under one-man rule.

“The end of the state of emergency does not mean our fight against terrorism is going to come to an end,” said Justice Minister Abdulhamit Gul.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Asaduddin Owaisi files nomination papers on Friday

Apr 20, 2024

Owaisi Begins Election Campaign in Hyderabad

Apr 13, 2024

Bring back Indian workers in Israel: Owaisi

Apr 13, 2024

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Ruturaj Gaikwad would be a good captain for Chennai Super Kings?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2024 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)